The following is an article describing my Connected Speech-based Approach (ConSpA) to pronunciation teaching and how to use it in teaching practice. This article may be cited as >>Euler, S.S. (2013). Teaching authentic pronunciation: A connected speech-based approach. Retrieved from www.sashaseuler.com/conspa<<.

Teaching authentic pronunciation: A connected speech-based approach

The study of pronunciation in ELT has a very turbulent history which has always been subject to numerous misconceptions. In 2010 Judy Gilbert reports a very illustrative anecdote from a conversation with a colleague about teaching pronunciation: “[In 2009] one of my colleagues quoted a fellow teacher as saying ‘But pronunciation is SO boring!’ and added her own conclusion: ‘I am quite sure that all she knew about teaching pron was minimal pair sound drills. Yes, quite boring for everyone, because they were on a path to nowhere’” (Gilbert 2010, p. 1). Pattern drills focusing on individual sounds were used as part of the audiolingual method and, indeed, have been shown to not only be of little effect (e.g. A. Brown 1995), but also to be in violation of the principles of communicative language teaching (e.g. meaningful interaction, authentic language use). Because pronunciation was so strongly associated with segmental drilling it has been deliberately neglected in CLT and even today many course books have no specific sections on pronunciation. Fraser (2000) describes that once the ELT community came to realize the importance of pronunciation, there were hardly any materials to turn to and linguistic treatments of phonetics and phonology are not easily made relevant for ELT purposes. She concludes that “it will be clear that there is a burning need for an increase in the amount of serious research at all levels to allow methods and policies to be assessed for their effectiveness” (ibid., p. 42).

Although many teachers around the world are not aware of the progress that has been made in pronunciation pedagogy, it is true that since the 1980s communicative and meaningful ways of teaching pronunciation were developed (see e.g. A. Brown 1991; Celce-Murcia et al. 2011) and that especially the communicative value of intonation gained recognition in ELT (e.g. Chun 2002). Intonation has grammatical functions such as marking a sentence as a statement or a question, it has discourse functions in that primary sentence stress marks old and new information or the focus word of a statement, it makes the stream of speech more processable for communication through marking thought group boundaries, and it provides crucial signals for turn-taking in conversation. Intonation can, further, be used to signal cooperation or compliance, to indicate expectations or to express emotional states. It should be obvious how such functions fit better into a communicative syllabus than individual sounds (compare Hurley 1992), especially since segmental problems like sound substitutions or certain “fuzzy” sound qualities can typically quite easily be interpreted from the context, while prosodic features operate on a more subconscious level and contribute to creating context.

Problems and needs

While such developments are laudable, there are still several problems with a predominantly intonation-based focus (see Euler forthcoming for a detailed discussion of approaches to pronunciation teaching). On a practical level I have often observed that practitioners teach intonation in a highly imitative fashion. Students are not guided to work on the ‘rules’ for marking tone unit boundaries, no help is provided for systematically mastering different pitch levels, and students do not understand why on some words there is supposed to be more pitch than on others. In interviews I have found that the few teachers who do in fact “dare” to teach pronunciation are not very comfortable with it because they a) do not know or understand the phonological facts behind it, and b) do not know how to utilize their language pedagogical knowledge for the teaching of pronunciation, in addition to the issues discussed above (see Euler in preparation b for ways of approaching this systematically).

On a more conceptual level, an important problem with this intonation-based approach is that pronunciation is more than just pitch contours. More recently some alternatives addressing this problem have been proposed such as Bertha Chela-Flores’ rhythm-based approach (e.g. Chela-Flores 1997, 2003) or Teschner & Whitley’s stress-based approach (Teschner & Whitley 2003). Others, like J.D. Brown (Brown & Kondo-Brown 2006, Brown 2013, forthcoming), Richard Cauldwell (Cauldwell 2013) and myself (Euler 2014, in preparation a) have worked, from different perspectives, on a connected speech-based approach as fully presented in this paper. Such alternative approaches recognize the enormous significance stress, rhythm and connected speech (as a result of the rhythmic timing) have in the phonological system of English. Practice in these areas will not only lead to more authentic and comprehensible production, but, as a psycholinguistic consequence, also to significantly enhanced listening comprehension skills (Vandergrift & Goh 2009, p. 339). Likewise, Celce-Murcia et al. (2011, p. 370) stress that “thought groups, prominence, stress (rhythm), and reduced forms” are of primary importance in developing student’s listening skills and that only practice in these areas can lead to “authentic listening comprehension”. On a more sociological level, non-compliance can, further, put significant strain on the listener which, in turn, has clear social and psychological consequences in that speakers may be perceived as rude, unintelligent, or dissocial, to name a few (see e.g. Munro 2008, Piske 2012, p. 42).

While such factors concern pronunciation teaching or prosody-focused pronunciation teaching in general, there are more reasons for putting particularly rhythm and connected speech in the center of attention. In Brown (forthcoming), J.D. Brown shares an anecdote about his teaching experience in China in 1981. He reports how one of his students asked him “Why is it that I can understand you when you talk to us, but cannot understand when you talk to another American teacher?”. He concluded that the teacher talk in class was quite different to authentic oral language rich in connected speech phenomena as used in the real world. My own path to this approach was quite similar. One of the first classes I taught years ago was a CAE (Cambridge Advanced English) exam preparation class. Since students were very advanced I decided to create a highly authentic task-based lesson sequence around an episode of a TV show. I was quite startled to find that even such highly experienced learners could hardly make any sense of the videos they were watching, some reporting a comprehension estimate of no more than 30%. I was very puzzled by this situation at the time since students were familiar with most of the grammar and vocabulary in these materials and did course book tasks of significantly higher levels of difficulty as regards vocabulary and syntax. When I repeated what the speakers in the videos said in ‘teacher talk’, students would understand everything perfectly. What I came to think is that this problem in comprehension was due to a difference in students’ mental representation of English (probably induced to some extent by unauthentic course book materials and a lack of feedback (compare Long 2009)) and the English that is spoken in the real world. Similar to J.D. Brown I soon came to realize that the problem lies in connected speech phenomena, which, in my own approach, is pedagogically addressed as a ‘logical’ product of the stress-timed rhythm of English.

In light of the various issues and needs discussed it is the aim of this paper to offer a full practical presentation of the Connected Speech-based Approach (ConSpA) to pronunciation teaching. This approach bears striking similarities with Michael Lewis’ Lexical Approach to the teaching of vocabulary (Lewis 1993, 1997) in that both approaches stress the power of chunking in language use and processing. The following section starts with a brief discussion of the notion of “approach” in language teaching and then expounds, in turn, how language, syllabus design and language learning are viewed and can be practically approached under a ConSpA framework. This will show how English stress-timing chunks the stream of speech through concatenation and how learners face this difficulty, it will illustrate how to use the interplay between various phonological domains to create a coherent pronunciation (sub)syllabus that can be implemented in an interactive, motivating and effective manner, and it will show how this can be realized in day-to-day teaching practice under communicative and task-based frameworks.

The Connected Speech-based Approach

In general terms, an approach is “the level at which assumptions about beliefs about language and language learning are specified” (Richards & Rogers 2001, p. 19). While classical approaches to language teaching (see ibid.) were about the language system as a whole, the same concept can be applied to language area-specific approaches (as in Lewis’ Lexical Approach), which provide an elaborate system for the teaching of vocabulary, pronunciation or grammar within a general communicative or task-based framework. In approaches, ‘beliefs about language learning’ includes psychological, language acquisitional and practical assumptions on how languages are learned and can be taught, while ‘beliefs about language’ refers to how the language is seen, i.e. what kinds of contents should be prioritized how. In addition to these two factors, Harmer (2007, p. 62) highlights a third aspect: “how language is used and how its constituent parts interlock”, which has clear implications for syllabus design (e.g. the prosody-centeredness as discussed above). In contemporary ELT it is agreed that approaches to pronunciation teaching should be centered on prosody (rather than individual sounds), but there is still considerable disagreement on which prosodic areas are most important, how they interlock and, in particular, how syllabi can be designed and materials developed addressing such assumptions. Once such a system is developed, many issues in implementation will arise. Along these lines, Gilbert (2010, p. 3) notes that

“[t]here need to be major changes in teacher training, materials available, appropriate supporting research, and changes in curricula. Most of the studies of teacher reluctance make clear that training should involve a more practical presentation of the subject, rather than what is essentially a catalogue of abstract concepts and terminology” (my emphasis).

The last sentence clearly calls for a systematic approach as presented here. In fact, throughout Brown & Kondo-Brown’s (2006) volume on teaching connected speech there are many calls for a systematic approach and the development of practical materials (e.g. Ito 2006, p. 25, Rogerson 2006, p. 94).

Views of language

Some of the reasons for a focus on connected speech were already discussed in the introduction. This section will address some further issues that prove to be valuable in teacher training and illustrate how rhythm and connected speech shape the steam of speech, and how to utilize this in teaching practice.

As Linell (2005) shows, traditionally language teaching was mainly concerned with the grammar of written English, with teachers and scholars being somewhat biased against forms of oral language. Speaking this kind of written English, however, seems quite unnatural, since spoken English is clearly different to what can helpfully be referred to as “written language spoken out”. Likewise, Avery & Ehrlich (1992, p. 73) introduce their chapter on connected speech as follows (my emphasis):

In this section, we describe the rhythm, stress, and intonation patterns of English phrases and sentences, and some of the modifications of segments that occur as a result of these patterns. If our students are to develop fluent, natural English, we must consider these aspects of pronunciation as they are essential to the production of connected speech.

This quote further emphasizes the point that connected speech is heavily intertwined with rhythm, stress and intonation, all aspects together shaping “natural” oral English. While it seems obvious that teaching should heed and utilize this interconnectedness, the question arises, then, why teaching connected speech still seems to be avoided. Aside the obvious lack of materials, course book components and respective language-pedagogical input in teacher training, a plausible reason may be the stigma of “bad English” often attached to forms of connected speech. During some recordings I produced with native speakers for an empirical study (Euler in preparation a), one informant proclaimed “gosh, what an ugly language we have” when I showed her some materials on regressive assimilation ([ɪʃi] – is she). Yet it has been shown time and again that connected speech is a very natural aspect of English that occurs in all registers. As the experimental phoneticians Ladefoged and Johnson (2010, p. 111) put it (see also Rogerson 2006, p. 93 for a similar applied linguistic account):

There is, of course, nothing slovenly or lazy about using weak forms and assimilations. Only people with artificial notions about what constitutes so-called good speech could use adjectives such as these to label the kind of speech we have been describing. Rather than being labeled lazy, it could be described as being more efficient in that it conveys the same meaning with less effort. Weak forms and assimilations are common in the speech of every sort of speaker of both Britain and America. Foreigners who make insufficient use of them sound stilted.

The number of connected speech features used will, therefore, not so much depend on the level of formality as on speaker style. Moreover, some aspects of connected speech like rhythm or linking, as will be shown presently, are relatively fixed (i.e. context-independent) either way and their non-realization will lead to the many consequences stated so far.

Another reason for the neglect of connected speech may be its non-salience, which is a problem for teachers as well as students. Since connected speech is especially strong in sequences of unstressed function words (e.g. might have been being pronounced [maɪDəvbɪn] or even [maɪDəbɪn]), individual phenomena typically go unnoticed and may very well cause this segment of the stream of speech to be simply incomprehensible. Related to this is the fact that phonological aspects like rhythmic timing and connected speech phenomena have little intrinsic communicative value in isolation (see Long & Robinson 1998 and Doughty & Williams (1998b) for aspects that can make a focus on form difficult). These phonological aspects, however, gain a lot of meaning through the way they interact in segmenting utterances. As Goh & Vandergrift (2009, p. 399) stress, even if learners know words, they may not recognize them in connected speech because they do not attend to stress, intonation and pause-boundaries adequately, also owing to the fact that word segmentation skills are L1 specific. This is especially so in rhythmically different languages (Cutler 2001), but it is important not to automatically assume that for speakers of other languages tending toward stress-timing rhythm will not be problematic. Chun (2002), for example, has shown instrumentally how English and German differ quite considerably in their realization of stress timing, again highlighting the powerful interplay between rhythm and connected speech (reduction, deletion and linking) in English. To illustrate, in a sentence like I met them at a party students could conceivably identify four chunks like “I medam ada party” (though there would normally be no real physical breaks and subjective native speaker perceptions of segmentation will differ.) Students may then well wonder why the speaker says madam and what ada means. Linguistically we can observe flapping of the inter-vocalic /t/, deletion (elision) of the th and, of course, linking. This is clearly rhythm-induced in that rhythmical stress is on met and party (and to a lesser extent on I). Therefore, [aɪˈmɛDəm] and [ˌæDəˈpaɹDi] can be seen as two rhythmical intervals, both part of one intonation unit (see Szczepek-Reed 2011). The big idea is that each of the two units, really, turns into a new three or four syllable word. Note that [aɪˈmɛDəm] and bewildered and [ˌæDəˈpaɹDi] and satisfaction, for example, have the exact same stress pattern. Rhythm creates new words, with the stressed (i.e. meaningful, or ‘content’ word) functioning like the (primarily) stressed syllable in a regular multi-syllable word. While other phonological features (sounds, intonation contours) have a somewhat limited distribution, rhythm and linking are omnipresent and unstressed function words will very often undergo some kind of reduction in connected speech. This actually has a very powerful rationale, discussed shortly, making students aware of which is essential in priming them for meaningful pronunciation work.

In teaching rhythm one way to build some initial awareness is with activities like tapping along sentence stress, for example taking a sentence like kids pat dogs and extending it to the kids pad the dogs, the kids may pat the dogs, the kids might have patted the dogs (Euler 2014). Students will easily notice that even though words are added, the timing remains the same. However, as particularly obvious in the rather extreme last sentence, this can only be done if we link and reduce the words somehow. Saying them one by one in citation form simply makes it physically impossible to maintain stress-timing. This can easily be used as an illustration of why comprehending authentic spoken English can be so difficult. Students’ own mental representation of the language may be so different that the incoming stream of speech simply cannot be processed (and will make students’ own pronunciation rather unauthentic, or perhaps even barely comprehensible).

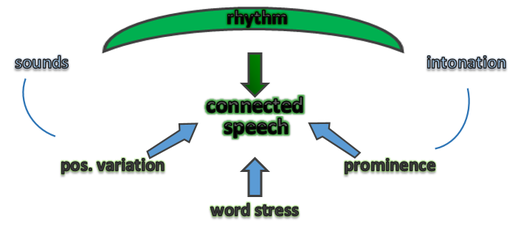

Figure 1 shows a graphical representation of the ConSpA (adapted from Euler 2014, p. 105). Connected speech takes its place in the center of the pronunciation teaching effort because it is conditioned by all other aspects and because language in connected speech is the final language product to be produced or to be comprehended. In the ConSpA rhythm stands as a kind of umbrella concept above everything else since it is a key component of any coherent utterance (as opposed to certain sounds or intonation patterns, which occur in more limited distribution). Linking seems comparable to rhythm in that within the boundaries of a rhythmical interval or even tone unit it is largely omnipresent. Likewise, Celce-Murcia et al. (2011, p. 165) define linking as “[t]he ability to speak English “smoothly”, to utter words or syllables that are appropriately connected” and note that “[e]ven to the linguistically naïve, a salient characteristic of much of nonnative English speech is its “choppy” quality”. In contrast, assimilation and deletion, though present in all registers, are somewhat more dependent on speaker style (Ladefoged & Johnson 2010).

In teaching practice the way stress-timing shapes language in connected speech is emphasized from the very beginning in the ConSpA and is illustrated in focus on form and feedback sessions on a regular basis (e.g. with listening extracts or with speaking activities, for instance as following grammar or vocabulary activities). Other aspects that receive priority are prominence (defined, with e.g. Celce-Murcia et al. (2011), as the allocation of primary sentence stress (nuclear stress) and the use of thought group (tone unit) boundaries), word stress and positional variation (e.g. the vowel length difference before voiced or voiceless consonants, as in bus vs. buzz or bat vs. bad). Intonation (in the narrow sense as final pitch movements) is often unproblematic if not fully correct (Chela-Flores 1997) and sounds mainly add to accentedness, but rarely impact comprehensibility in context (Munro & Derwing 1995). Lessons or input sessions on these two aspects are provided rather incidentally when the topic arises or as part of some feedback, but receive minor attention (i.e. classroom time allocation) in comparison. At this point it should also be noted that this approach is an ESL/EFL approach designed to facilitate NNS-NS interaction and is not to be confused with ELF (international English for NNS-NNS communication) (Jenkins 2000, Walker 2010).

Views of how language constituents interlock (syllabus design)

The next question, obviously, is how to realize this concept in a given ESL/EFL program and how to integrate it into curricula and course books. Michael Long (e.g. Long & Robinson 1998, Long 2000) proposed the distinction between three types of syllabi, focus on meaning, focus on form (both analytic) and focus on forms (synthetic). The analytic approaches are opportunistic and grow out of tasks which students are involved in (rather than being pre-determined by a book or curriculum), the latter case typically being characteristic of a synthetic focus on forms. This is based on the fact that in ‘traditional’ language teaching syllabi were designed around forms, which were taught in isolation and out of context simply because they were on the plan. Focus on meaning (in Long’s sense) is the opposite extreme and promotes a non-interventionist view according to which with enough comprehensible input language learning will take care of itself (e.g. Krashen & Terrell 1983). When this is of limited effect in grammar and vocabulary learning, it is hardly of any use at all in pronunciation teaching, where, due to the low perceptual salience of many phonological features, a more explicit focus on form is necessary. According to Long, focus on form syllabi are organized around real-world communication topics and try to follow the internal psycholinguistic learner syllabus (see Doughty & Williams 1998b, Long 2009 for a discussion). Generally, forms are more in tandem with learners’ internal syllabi when students are motivated to attend to certain forms because they are problematic or needed in a given situation (Long 2009, p. 384f). This need, motivating a “shift of attention to linguistic code features – by the teacher and/or one or more students – [is] triggered by perceived problems with comprehension or production” (Long & Robinson 1998, p. 23), which is exactly the rationale behind the syllabus proposed here: once students see the impact English rhythm and everything connected to it has on comprehensibility of L1 English (or on the authenticity of their own production if that is of personal concern), a real need will be perceived.

While Long would have it mainly reactive in drawing learners’ attention to formal problems only as they arise in class, a more proactive (pre-planned by the teacher) stance is also well justified (Doughty & Williams 1998b) if it provides prerequisite engagement in meaning. This is analogous with designing an engaging task-cycle about future plans with the intention of introducing going to alongside developing (some of the) four skills, or doing the same with texts on financial assets because the teacher sees this kind of vocabulary as useful at that stage.

The connected speech syllabus as described below should be seen as a sub-syllabus to handle pronunciation in a normal skills-focused language course. It can, however, also be used for intensive courses on pronunciation and oral fluency in which units may have phonological topics (bearing the appearance of a focus on forms), but are taught in a meaningful and communicative fashion (i.e. by selecting activities and materials that are conducive for teaching certain pronunciation points).

The syllabus of the present approach follows the following structure (see Euler 2014, p. 106 for a graphical model):

Prosody --> Connected speech: Reduction & deletion --> Connected speech: Linking --><-- Sounds

Owing to the facts discussed above, establishing the prosodic groundwork and using the cyclicality of such omnipresent features helps prime learners for connected speech. Connected speech is comprised of a vast number of individual phenomena with little communicative purpose in isolation, which would make them virtually unteachable in any meaningful manner. This syllabus tries to solve this problem by helping students to truly understand and appreciate how prosody is realized in authentic speech (i.e. how speech is segmented into tone units and rhythmical intervals and how this causes chunking, i.e. how words fuse in ‘stress valleys’). After prosody has been studied for a while students will have come across connected speech phenomena (not yet explicitly discussed with individual rules, but sometimes produced) many times in meaningful contexts. By the time these phenomena are explicitly discussed students are highly aware of their context, distribution and ‘logic’. Students, further, have clear impressions of how connected speech can be realized because their attention was drawn to various processes in context and because they occasionally used them in focused production tasks (which further facilitates awareness (Larsen-Freeman 2003, p. 104f)). Connected speech may then well be discussed more explicitly by highlighting “rules and reasons” (Larsen-Freeman 2003) as we would with grammar. Such rules are, for example, that when /t, d/ is followed by /y/, these sounds merge and become /tʃ/ and/dʒ/, respectively (called coalescent assimilation), as in Wouldcha do that?.[1] While this would seem random and teacher-imposed without the first stage, after having come across such features in the context of prosody students often actually want to know the rules, they are so primed for what happens in what can pedagogically be called ‘stress valleys’ that supplementing the rules, with pedagogical sensitivity, will actually fulfill a real need students have by that time. This is, again, much of the basis of task-based and focus on form instruction, in this case realized over a whole teaching program as a pronunciation sub-syllabus.

Linking, generally, is an extremely difficult topic to teach because of its low salience and the amount of individual rules. This problem is also eased through the preparatory nature of the preceding pronunciation lesson components, but can be systematically addressed by subsuming the individual rules under larger topics. These can usefully be “words fuse” (are pronounced like one polysyllabic word), “words fuse through glide (/w, j/) insertion” (see-y-it), “through sound change” (assimilation) or “though flapping” (pronouncing intervocalic /t/ like a short /d/), which covers every possible case. For example, treating regressive assimilation and flapping (in NAmE, in BE glottal stops may be an issue) as components of linking (psychologically) reduces the number of individual things to be learned drastically and gives it (or by giving it) some inherent context and logic, all of which making the topic a lot less intimidating.

Sounds, finally, are explicitly discussed later in the course or teaching program or are supplemented whenever the need arises (compare Gilbert 2012). Such needs can have various bases and do arise occasionally, for example when students show an interest in a particular phenomenon the teacher highlights because they implicitly realized there is ‘something there’ but could not put their finger on it, when they notice certain BE/NAmE differences, when they feel they would like to standardize their own sound production according to BE/NAmE norms, or when they desire to correct mistakes they became aware of now that they, generally, started paying attention to pronunciation. Especially in EFL contexts I have found it helpful to introduce vowel sounds through the topic of British and American English differences since this often causes confusion.

As regards students’ level, personally I have used this system with learners on all levels from EFL beginners (using monolingual explanations at times) through proficiency, and I have found it to be very motivating and effective on all levels because it is equally needed on all levels (see Euler in preparation a for an empirical verification of the ConSpA and other relevant empirical evidence). Naturally, this structure suggested here is simply one that turns out to be effective, but is not carved in stone and may be varied in local teaching contexts as long as its general logic is preserved.

Views of leaning

As noted in the introduction, it is often difficult for teachers to apply their language pedagogical knowledge to pronunciation teaching. Teaching pronunciation, is, indeed somewhat more complex than teaching grammar and lexis, but many principles of focus on form instruction are essentially the same and can be adapted without having to ‘re-invent the wheel’. This section discusses basic aspects of both communicative and task-based pronunciation teaching.

A communicative framework for pronunciation teaching

The classical model for communicative grammar lessons goes from analysis to guided practice to free practice (e.g. Savage 2010). This is what Jeremy Harmer refers to as the straight arrows model. Two alternatives Harmer proposes are the boomerang model and the patchwork model (Harmer 2007, p. 67). The first (similar to task-based teaching) turns the steps upside-down. With non-salient features this is especially useful for practicing already basically established information, e.g. adding aspects of intonation or connected speech after the concepts of pitch and rhythm, respectively, were already established in previous lessons. The patchwork model repeats those steps several times in somewhat random order as needed in a particular case. This seems especially useful for teaching linking. Marianne Celce-Murcia (Celce-Murcia et al. 2011, p. 45ff) developed a basic model to be used in such manners for pronunciation:

- Description and Analysis – oral and written illustrations of how the feature is produced and when it occurs within spoken discourse

- Listening Discrimination – focused listening practice with feedback on learners’ ability to correctly discriminate features

- Controlled Practice – oral reading of minimal-pair sentences, short dialogues etc., with special attention paid to the highlighted feature in order to productively develop learners’ consciousness

- Guided Practice – structured communication exercises, such as information-gap activities or cued dialogues that enable the learner to monitor for the specific feature

- Communicative Practice – less structured, fluency-building activities (e.g., role play, problem solving) that require the learner to attend to both form and content of the utterance.

The listening and controlled practice phases are not normally found in comparable grammar teaching models, but are very important for many aspects of pronunciation. As regards listening discrimination, a large body of research in second language speech perception has shown that learners are not always able to orally perceive non-native sounds and often assimilate them to native categories and perceive them as such (e.g. Flege 1995 or Best & Taylor 2007). Pitch levels and movement also needs considerable perceptual training since the exact pitch-duration-loudness ratio used to mark stress differs considerably from language to language, which can easily communicate unintended emotional states like angriness, nervousness or boredom, in addition to not marking the sentence focus adequately. Developing students’ perceptive skills is, further, important since it can turn out very frustrating if they are asked to produce features they cannot orally discriminate (Celce-Murcia et al. 2011, p. 46). Focused listening will help students identify features and distinguish them from similar/conflicting ones. For example, learners could work on distinguish /l/ from /ɹ/ or /ɛ/ from /æ/, in a lesson on speech rhythm they could be asked to mark all the words that receive sentence stress, and in a lesson on intonation they could draw in curves for rising or falling intonation on text transcripts.

Controlled practice extends analysis and listening discrimination with consciousness-raising through production and in order to learn to actually articulate new phonological features. Celce-Murcia et al. (2011, p. 43) point out that “[t]eaching pronunciation is unlike teaching grammar or vocabulary in that, in addition to teaching rule-based features of language, pronunciation teachers must also cope with the fact that pronunciation is a motor activity [and] poses sensory and physical challenges to the leaner, not just cognitive challenges”. Therefore an “extra” phase is well justified. This is supported by the fact that while it has been shown that some features need very little pedagogical focus, features in which it is difficult to construct the form (which again certainly seems true for rhythmic timing, pitch movement, concatenation or L1 assimilated sounds) need explicit practice and repetition in a meaningful (i.e. task-essential) way (Fotos 2002, Samuda 2001). Controlled practice will allow learners to monitor their own articulation from short-term memory so that it may become more automatic in time. The focus here is on form and accuracy and teachers need to intervene if production is continuously unsuccessful (e.g. in pair or group work with students monitoring themselves and each other). Such practice could comprise reading minimal pair sentences or short dialogues, or even poems and jazz chants for stress and rhythm (Vaughan-Rees 2010). Note that this is the only place in which reading out is really an appropriate technique in pronunciation teaching; if the focus is not fully on monitoring, reading will probably lead to unnatural production or to reading without internalization (compare Celce-Murcia et al. 2011, p. 11).

The other phases are well-known from grammar teaching and need no further elaboration. What perhaps needs extra stressing is that it is essential for students to also experience real operating conditions in order to internalize structure (e.g. Larsen-Freeman 2003, p. 121). Analysis, listening discrimination and controlled practice are often all that is found in pronunciation classrooms, but will be of limited effect alone. Guided and free practice, therefore, must not be neglected. It should perhaps also be highlighted that in communicative practice “interactions may include more than just the target grammar, and students are freer to choose the context of their utterances” (Savage 2010, p. 33).

A task-based focus on form framework for pronunciation teaching

Some of the basic tenants of task-based focus on form methodology were already established in the context of syllabus design. As Long (1991, p. 45f) put it, “focus on form […] overtly draws students’ attention to linguistic elements as they arise incidentally in lessons whose overriding focus is on meaning or communication”. It has been said that this can also be proactively planned for by the teacher so that communicative needs will actually arise. Doughty & Williams (1998b) utilize Loschky & Bley-Vroman’s (1993) distinction between task naturalness (features may arise but are not necessary for the task), task utility (with the feature the task becomes easier) and task essentialness (the feature is necessary for the completion of the task) to illustrate the decision-making process in the proactive stance. Doughty & Williams (1998b, p. 209) argue that “task essentialness can more easily be incorporated into comprehension tasks, whereas production tasks may only rarely go beyond task naturalness or task utility”. This is clearly one of the guiding principles of the ConSpA as has been shown. Communicative needs arising through genuine problems with comprehension or production create a cognitive window of opportunity for language learning. In other words, in this situation focusing on form is not only highly motivating (ideally owing to their task-essentialness), but also makes the following contents potentially a lot more processable and therefore teachable. In task-based teaching (TBT), meaning is primary, there is some communication problem to be solved which is similar to comparable real-world activities (Skehan 1998, p. 95), or at least to real-world meaning and discourse (Willis & Willis 2007, p. 15).

These factors can be summarized for pronunciation teaching in the following way: In pronunciation teaching genuine communicative needs, which are imperative in building intrinsic motivation (compare Euler in preparation b), can easily be found in the way stress-timed rhythm makes listening comprehension so difficult. Once students are made aware of why comprehension is difficult, once they understand that in order to maintain the rhythmic timing things have to happen in ‘stress valleys’, and that these things are highly systematic and rule-based, they will have clear goals which can be made systematically achievable. This is very motivating because it creates a real need out of genuine engagement in meaning (trying to extract meaning from NS speech). This is a very productive starting point for task-based pronunciation teaching.

A basic model for TBT lessons is illustrated in figure 2 (after Willis & Willis 2007, p. 24f). Obviously, parts of the sequence can be repeated in longer task-cycles. In practice, any engaging topic that has significance for students’ lives (real-world meaning) that is worth discussing, selecting things from/for, reporting, voting on, sharing opinions about, solving problems based on or deciding upon (real-world discourse) is worth selecting (though often institutional curricula pre-determine certain topics, often based on certain vocabulary or grammar items that are to be taught). Still, it is very much feasible to make respective topics into a TBT sequence. For pronunciation it is especially helpful to work with listening extracts (ideally from videos to add further authenticity) that students discuss, select things from, categorize and work with in whatever way works for the topic, is meaningful and leads to specific outcomes. At the end of such a cycle students would have watched the scenes/extracts several times and would have experienced real comprehension problems at times (teachers would select recordings or videos where speaking rate, rhythm and connected speech are highly authentic). In focus on form tasks students may now well want to know why they did not understand certain things and how to do better in the future. Teachers could then work with transcripts, for example, and have students listen for aspects like tone units (with respective continuation rises and low falls) and tone unit boundaries, or she could have them mark sentence stress (rhythmically stressed words) and then compare again with the video. Students could, further, mark connected speech phenomena, maybe on sequences of words highlighted by the teacher or previously predicted by the students themselves if they already understand the concepts well (i.e. are able to predict that in e.g. nine out of ten of them something must happen to the unstressed function words, at the very least vowel reduction and linking, but probably also deletion). This might, then, be followed by more specific production tasks to further practice these features if deemed necessary and if motivation can be maintained. It should, however, be noted that even in more receptive tasks there are production components. If students work in pairs or small groups on identifying phonological features in a video transcript, they will produce these features as they are negotiating which words are stressed, for example. In a task-based framework, production exercises should always be clearly contextualized, meaningful and organically related to the other components of the task-cycle.

Conclusion

It was the purpose of this article to expound a new way of approaching the teaching of pronunciation. After general needs and issues were established the first step was to demonstrate how the various components of English phonology work together to structure the stream of speech into meaningful units. The part on syllabus design, then, illustrated how to implement this approach in given curricula and language programs, and how to logically sequence various individual aspects so they become processable. Finally, two current frameworks for actual lesson planning and materials development were presented. All parts together make it possible to teach English pronunciation in a contextualized, organic, meaningful and motivating manner. This will help students to develop full communicative competence (D. Brown 2007, p. 339) not only by being understood easily, but by being able to understand native speakers well.

While the ConSpA was developed as a state-of-the-art approach that attempted to address current developments and needs in pronunciation teaching and to consider the current state of knowledge in syllabus design and teaching methodology, a number of aspects are still clearly in need of further exploration. One of the greatest gray-zones in pronunciation pedagogy is the notion of “task-based pronunciation teaching”, which is still barely existent. While task-based methodology is not easy to harmonize with the specific difficulties in pronunciation acquisition, the Connected Speech-based Approach is founded on principles that are very much in line with the basic tenants of TBT. Therefore, utilizing the ConSpA framework might open up a new path into task-based pronunciation teaching. In a similar way pronunciation is still absent from most teaching programs, often since course books have no specific pronunciation components. It has been shown that this is probably because pronunciation is still considered by many to be overly technical, boring and therefore not suitable for communicative language teaching. The present approach should make it better possible to exploit materials for contextualized and meaningful pronunciation practice, and the proposed syllabus can help to make pronunciation an organic component of any teaching program. On a more general level, it would be interesting to see how teachers develop materials, techniques and lessons according to particular needs in their specific local contexts, in the same way as the approach would benefit from further empirical validation in various contexts or institutions.

References

Avery, P.W. & Ehrlich, S. (1992). Teaching American English pronunciation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baker, A. & Goldstein, S. (2008). Pronunciation pairs (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Best, C.T. & Tyler, M.D. (2007). Nonnative and second-language speech perception: Commonalities and complementarities. In O.-S. Bohn & M.J. Munro (Eds.), Language experience in second language speech learning (pp. 13-34). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Breitkreutz, T., Derwing, T.M. & Rossiter, M.J. (2001). Pronunciation teaching practices in Canada. TESL Canada Journal, 19, 51-61.

Brown, A. (Ed.) (1991). Teaching English pronunciation: A book of readings. London: Routledge.

Brown, A. (1995). Minimal pairs: minimal importance? ELT Journal, 49, 169-175.

Brown, J.D. (Ed.) (2013). New ways in teaching connected speech. Alexandria: TESOL.

Brown, J.D. (forthcoming). Shaping students’ pronunciation: Teaching the connected speech of North American English. Unpublished ms. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii at Manoa.

Brown, J.D. & Kondo-Brown, K. (Eds.) (2006). Perspectives on teaching connected speech to second language speakers. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Brown, H.D. (2007). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy (3rd ed.). White Plains, NY: Addison Wesley Longman.

Cauldwell, R. (2013). Phonology for listening: Teaching the stream of speech. Birmingham: SpeechinAction.

Celce-Murcia, M, Brinton, D.M. & Goodwin J.M. (2011). Teaching pronunciation: A course book and reference guide (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chela-Flores, B. (1997). Rhythmic patterns as basic units in pronunciation teaching. ONOMAZEIN, 2, 111-134.

Chela Flores, B. (2003). Optimizing the teaching of English suprasegmentals to Spanish speakers. Lenguas Modernas, 28-29, 255-274.

Chun, D.M. (2002). Discourse intonation in L2: From theory and research to practice. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

Cutler, A. (2001). Listening to a second language through the ears of a first. Interpreting, 5, 1-23.

Derwing, T.M., Munro, M.J. & Wiebe, G.E. (1998). Evidence in favor of a broad framework for pronunciation instruction. Language Learning, 48, 393-410.

Derwing, T.M., Rossiter, M.J. (2003). The effects of pronunciation Instruction on the acquisition, fluency, and complexity of L2 accented speech. Applied Language Learning, 13, 1-17.

Doughty, C.J. & Williams, J. (Eds.) (1998a). Focus on form in classroom second language acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Doughty, C.J. & Williams, J. (1998b). Pedagogical choices in focus on form. In C.J. Doughty & J. Williams (Eds.), Focus on form in classroom second language acquisition (pp. 197-261). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Euler, S.S. (2014). Implementing a connected speech-based approach to pronunciation teaching. In T. Pattison (Ed.), IATEFL 2013 Liverpool conference selections (pp. 104-106). Canterbury: IATEFL.

Euler, S.S. (forthcoming). Approaches to pronunciation teaching: History and recent developments. In E. Guz (Ed.), Recent developments in applied phonetics (Studies in linguistics and methodology) (pp. XXX). Lublin: University of Lublin Press.

Euler, S.S. (in preparation a). Testing the effectiveness of a connected speech-based approach in advanced EFL pronunciation teaching.

Euler, S.S. (in preparation b). Three maxims and ten principles of successful pronunciation teaching: The state of the art and a way forward.

Flege, J.E. (1995). Second language speech learning: Theory, findings, and problems. In W. Strange (Ed.), Speech perception and linguistic experience: Issues in cross-language research (pp. 233-277). Timonium, MD: York Press.

Fotos, S. (2002). Structure-based interactive tasks for the EFL grammar learner. In E. Hinkel & S. Fotos (Eds.), New perspectives on grammar teaching in second language classrooms (pp. 135-154). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Fraser, H. (2000). Coordinating improvements in pronunciation teaching for adult learners of English as a second language. Canberra: DETYA.

Giegerich, H. (1992). English phonology: An introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gilbert, J.B. (2010). Pronunciation as orphan: What can be done? As We Speak, 7, 1-9.

Gilbert, J.B. (2012). Clear speech. Pronunciation and listening comprehension in American English (4th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Harmer, J. (2007). The practice of English language teaching (4th ed.). Harlow: Longman.

Hurley, D.S. (1992). Issues in teaching pragmatics, prosody, and non-verbal communication. Applied Linguistics, 13, 259-281.

Ito, Y. (2006). The significance of reduced forms in L2 pedagogy. In J.D. Brown & K. Kondo-Brown (Eds.), Perspectives on teaching connected speech to second language speakers (pp. 17-26). Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Jenkins, J. (2000). The phonology of English as an international language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Krashen, S.D. & Terrell, T.D. (1983). The natural approach. New York: Pergamon Press.

Ladefoged, P. & Johnson, K. (2010). A course in phonetics (6th ed.). Boston: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2003). Teaching language: From grammar to grammaring. Boston: Heinle.

Lewis, M. (1993). The lexical approach: The state of ELT and a way forward. Boston: Heinle.

Lewis, M. (1997). Implementing the lexical approach. Boston: Heinle.

Linell, P. (2005). The written language bias in linguistics. London: Routledge.

Long, M.H. (1991). Focus on form: A design feature in language teaching methodology. In K. de Bot, R.B. Ginsberg & C. Kramsch (Eds.), Foreign language research in cross-cultural perspective (pp. 39-52). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Long, M.H. (2000). Focus on form in task-based language teaching. In R.H. Lambert & E. Shohamy (Eds.), Language policy and pedagogy (pp. 179-192). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Long, M.H. (2009). Methodological principles for language teaching. In M.H. Long & C.J. Doughty (Eds.), The handbook of language teaching (pp. 373-394). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Long, M.H. & Robinson, P. (1998). Focus on form: Theory, research and practice. In C.J. Doughty & J. Williams (Eds.), Focus on form in classroom second language acquisition (pp. 15-41). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Munro, M.J. (2008). Foreign accent and speech intelligibility. In J.G. Hansen Edwards & M. L. Zampini (Eds.), Phonology and second language acquisition (pp. 193-219). Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Munro, M.J. & Derwing, T.M. (1995). Foreign accent, comprehensibility, and intelligibility in the speech of second language learners. Language Learning 45, 73-97.

Richards, J.C. & Rodgers, T.S. (2001). Approaches and methods in language teaching (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rogerson, M. (2006). Don’cha know? A survey of ESL teachers’ perspectives on reduced forms instruction. In J.D. Brown & K. Kondo-Brown (Eds.), Perspectives on teaching connected speech to second language speakers (pp. 85-97). Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Piske, T. (2012): Factors affecting the perception and production of L2 prosody: Research results and their implication for the teaching of foreign languages. In J. Romero-Trillo (Ed.): Pragmatics and prosody in English language teaching. Heidelberg/New York/London: Springer.

Samuda, V. (2001). Getting relationships between form and meaning during task performance: The role of the teacher. In M. Bygate, P. Skehan & M. Swain (Eds.), Task-based learning, language teaching, learning and assessment (pp. 119-140). Harlow: Pearson.

Savage, K.L. (2010). Grammar matters: Teaching grammar in adult ESL programs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from http://www.cambridge.org/us/esl/satellite_page/item2493274/teacher-support-plus/

Skehan, P. (1998). A cognitive approach to language learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Szczepek-Reed, B. (2011). Analyzing conversation: An introduction to prosody. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Teschner, R.V. & Whitley, M.S. (2004). Pronouncing English: A stress-based approach. Plymouth: Plymbridge Distributors Ltd.

Vandergrift, L. & Goh, C. (2009). Teaching and testing listening comprehension. In M.H. Long & C.J. Doughty (Eds.), The handbook of language teaching (pp. 395-411). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Vaughan-Rees, M. (2010): Rhymes and rhythm: A poem-based course for English pronunciation study. Reading: Garnet Education.

Walker, R. (2010). Teaching the pronunciation of English as a lingua franca. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Willis, D. & Willis, J. (2007). Doing task-based teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[1] See Baker & Goldstein (2007), Celce-Murcia et al. (2011) or Gilbert (2012) for pedagogical presentations of the rules of English pronunciation or Giegerich (1992) and Szczepek-Reed (2011) for very clear linguistic accounts.